At the end of the 1960s, the city of Montreal was flying high. It had been the site of Expo 67, a World’s Fair that had attracted millions of visitors. The event had boosted the image of Montreal as a progressive urban center on par with any other major metropolis. And in the process, it had changed the face of the city. Expo 67 had been the pet project of Mayor Jean Drapeau, who had made it happen against all odds. I mean that quite literally, as a computer program had projected that it could never be completed on time. With that type of success under his belt, Drapeau moved onto the next project. However, he had little idea just how disastrous things were about to get.

The Big Owe

In general, it’s pretty much enshrined in local history that both the preparation and the aftermath of the 1976 Montreal Olympics were a complete and total catastrophe. Canada indeed had fought hard to make the city the host for the summer games, with the International Olympic Committee accepting their bid in 1970. However, from there, things spun quickly out of control. It’s rare for an Olympic host city to run under budget, but Montreal is perhaps the most egregious example of this. Costs ballooned to $1.4 billion from an initial budget of $207 million—a debt that would take Montreal three decades to pay off. But why?

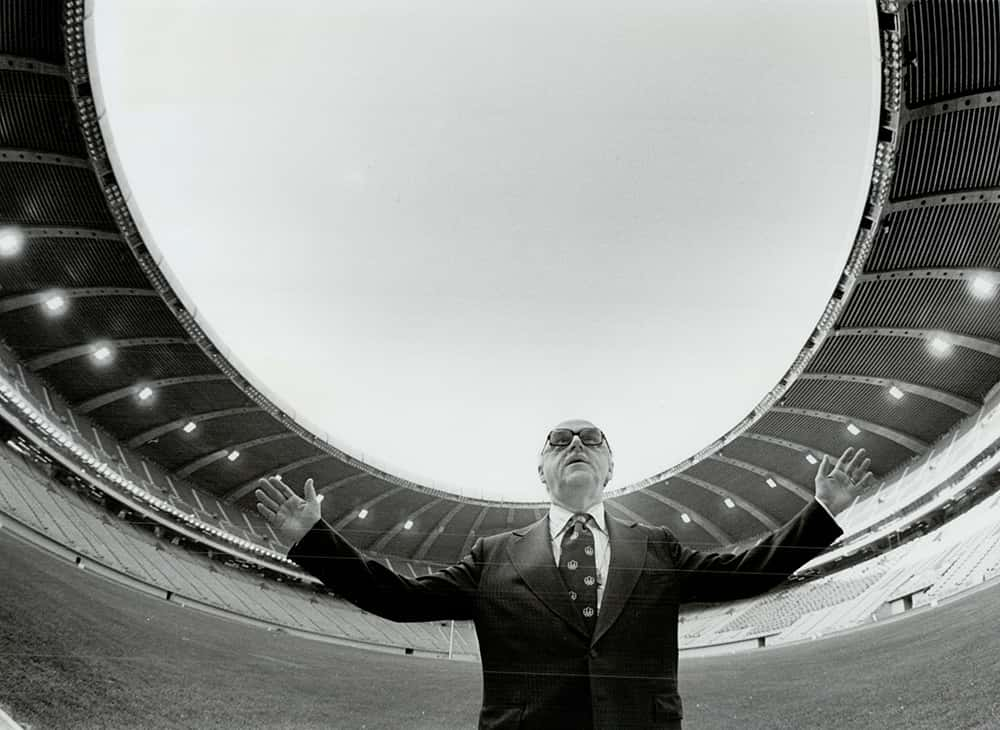

Getty Images Mayor Jean Drapeau waves a specially-made flag with the emblem of the 1976 Olympic Games.

Getty Images Mayor Jean Drapeau waves a specially-made flag with the emblem of the 1976 Olympic Games.

Well, in typical Montreal fashion, a corrupt union official held the preparation hostage, driving up costs. Drapeau did what he could to keep everything in line, but it was too late. In 1975, the provincial government took over everything, leaving Drapeau on the sidelines. It was a hard blow to his ego. Drapeau was left grappling for control where he could find it. His pathetic grasp began with pointless cosmetic overtures. He banned newspaper boxes and hot dog vendors—and then it turned sinister.

The Birth Of Corridart

Montreal-born artist and architect Melvin Charney had worked in Paris and New York before making the journey back to his hometown in 1964. In the decade and a half that followed, he watched as Expo 67 and the preparations for the 1976 Games transformed the city—both for better and for worse. Part of this had been the clearing of slums and the planned demolition of historic buildings on Sherbrooke Street, a major corridor that abutted the site of the Olympic Stadium.

The Games’ organizing committee, now led by the province, put aside a budget for an arts & culture program. The committee invited Charney to become the organizer and coordinator of a major event. He called it Corridart, and the plan was for it to transform a 5.5km stretch of Sherbrooke Street. They would make it into a temporary, open air museum featuring a plethora of works by Quebec artists in different mediums. It would help draw tourists from the eastern part of the city where the Stadium was toward the downtown core. He had the idea, the plan, the budget, and dozens of artists ready to participate. However, Mayor Drapeau had other ideas.

Corridart And The City

Together with Charney, 35 different artists prepared works for Corridart. Some were ephemeral, like performances that would take place along the route. Others were monumental, like Bill Vazan’s 500,000 lb. stone maze or Pierre Ayot’s scale replica of Mont Royal’s famed cross, laid on its side. Despite its provincial backing, there was little-to-no political interference with the content of Corridart. The exhibition pulled no punches when it came to risqué, controversial, and political content. Many of the works directly addressed the socio-economic problems of the city.

Flickr Melvin Charney, Houses of Sherbrooke Street

Flickr Melvin Charney, Houses of Sherbrooke Street

Charney’s most significant work in the exhibition was called Houses of Sherbrooke Street. It was an architectural installation that featured empty facades of historic buldings supported by scaffolding. It faced out onto a street where so many structures had been heartlessly demolished in favor of concrete towers. The work seems to reflect on Mayor Drapeau’s approach to presenting the city as a glittering yet empty façade, and how he had failed its residents in the process.

An Army Of One

The artists and their teams finished putting up the work for Corridart on July 6, 1976. This was well in advance of the official opening of the Games and the exhibit. Charney and Corridart had the blessing and cooperation of the City of Montreal, the Games’ organizing committee, and their security committee. Did Mayor Drapeau actually attend the exhibition? Did he walk or drive by? Or did he just see photos of it in the paper and read the preliminary reviews? It’s unclear, but one thing is for sure. It hit him right where it hurts—in the ego. As he said himself, “I was shocked, I was humiliated, I was insulted.” Not everything is about you, Jean…

With less than 72 hours until the opening ceremonies, Mayor Drapeau did the unimaginable—and the completely illegal. When night fell, he sent city workers in with trucks and equipment to dismantle the entire exhibition. On his orders, police stood by to protect them. As they worked, the word spread. Artists began to arrive and attempt to salvage their works. Officers prevented them from even approaching. By the morning, they had completely decimated the 5.5 km Corridart stretch and had either impounded the remains or carted them off to the dump.

No Fury Like A Man Humiliated

Getty Images Mayor Jean Drapeau

Getty Images Mayor Jean Drapeau

By taking the Olympics away from him, the provincial government had robbed Drapeau of power, agency, and, most importantly to him, attention. The destruction of Corridart was simultaneously an attempt to exert the power he thought he deserved, a vicious temper tantrum, and an unprecedented act of censorship. But he didn’t stop there. Despite the controversial and illegal nature of the decision, City Hall fell in line behind him. As a result, the city held onto the Corridart artworks, although they had no right to do so. So, on top of the horrific act of censorship, it was also a heist to the tune of $386,000 worth of art—equivalent to about $1.6 million in 2017.

As a result, artists fought back any way they could, and it sparked a brutal legal battle that ultimately took ten years. The city eventually offered the artists a paltry $85,000 settlement. Additionally, those who did get their works back had to wait nearly four years. Sadly, for many artists, city workers had destroyed a significant number of artworks while dismantling the exhibition.

From Temporary To Unforgettable

Since the moment he'd come up with the idea for Corridart, Charney had always intended for its works to be temporary. However, in the long term, Drapeau’s overnight theft made it a victim of the Streisand Effect, where an act of censorship only serves to call further attention to its subject. Much has been made of the controversy, and it's been the subject of documentaries, retrospective exhibitions, and recreations of the works.

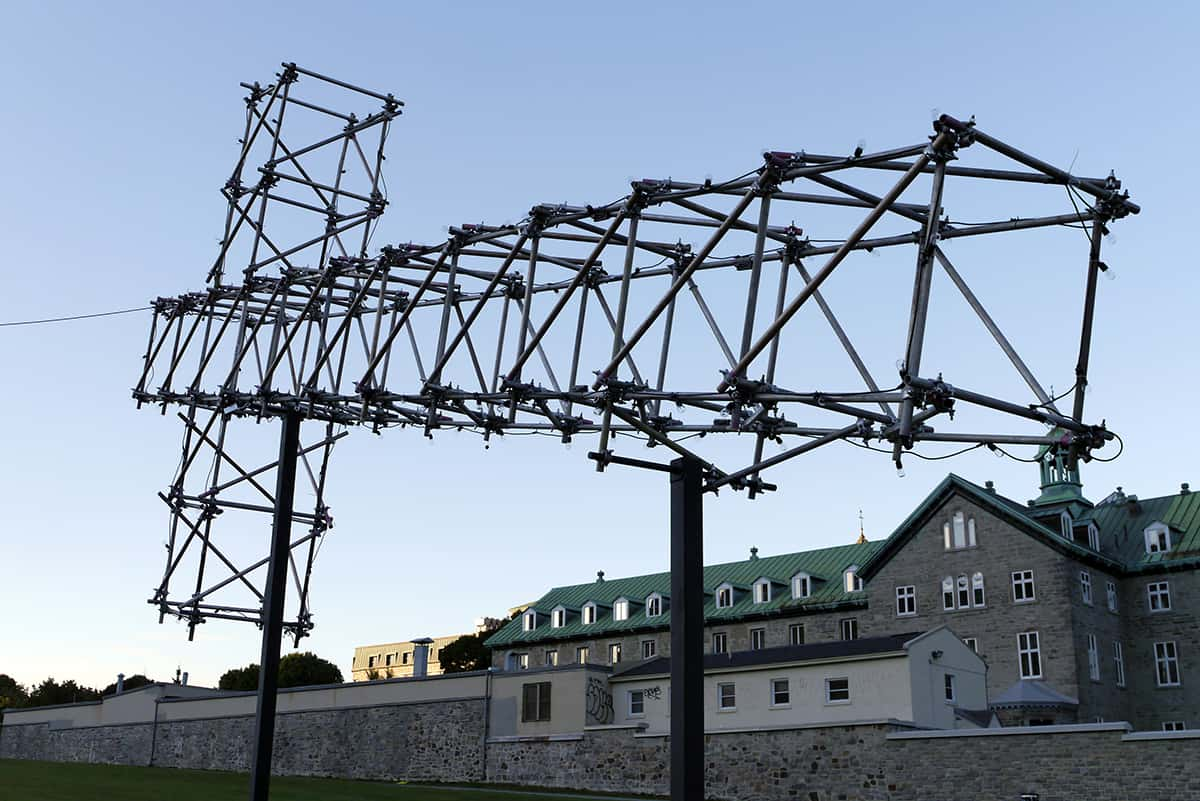

For example, Pierre Ayot recreated his La Croix du Mont Royal in 2016. Unsurprisingly, it drew ire from another egomaniac Montreal mayor, Denis Coderre. He then tried to cancel the grant that was going to fund it. Coderre claimed that its proximity to a local religious order was a problem. He never really checked with them—they didn’t care.

Wikimedia Commons Pierre Ayot, La Croix du Mont-Royal (replica), 2016

Wikimedia Commons Pierre Ayot, La Croix du Mont-Royal (replica), 2016

Ego Tripped

Similarly, Drapeau lied through his teeth to get rid of Corridart. He specifically said it was ugly and obscene. It wasn’t. Although it could hardly be considered harsh, he couldn’t take the criticism. Moreover, neither could the developers who Charney’s work targeted—the same ones who lined Drapeau’s pockets. And sadly, in a sense, it consequently worked out perfectly for him. It’s impossible to teach a narcissist a lesson in the best of circumstances, and the backlash to Drapeau’s big heist gave him the attention he so craved.

Despite the controversies and the monumental financial loss of the Olympics, Drapeau stayed mayor for another decade. As the mayor of a notoriously corrupt city, he accordingly saw zero consequences for anything he did. Eventually, the city settled the court case...but only after Drapeau left office. Up until the day he died, Drapeau never apologized for what he did at Corridart, one of the largest acts of arts censorship in Canadian history.